A Brief History of The Yardbirds, According to Drummer Jim McCarty

"Jimmy was cool...he had it all worked out. Eric would be very sulky. Jeff was the best."

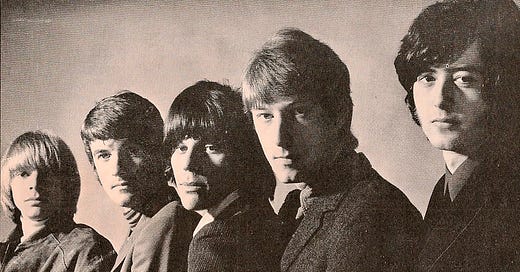

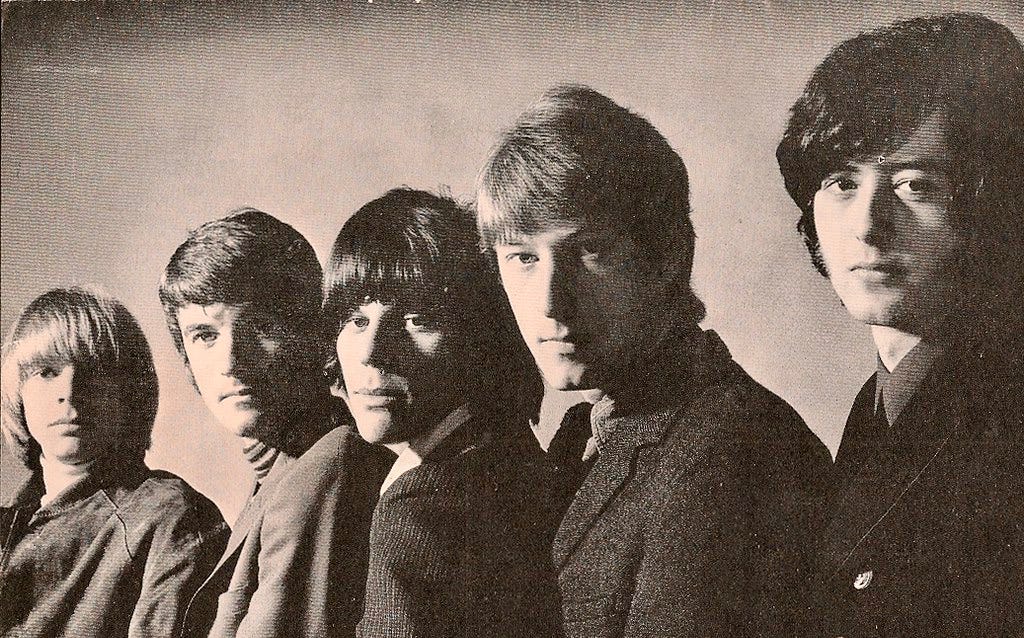

Long before Disraeli Gears, Blind Faith, and Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs convinced people that Eric Clapton was some kind of “God.” Before the pub-inspired proto-metal of Beck-Ola, and the avant jazz of Blow By Blow signaled the true genius of Jeff Beck. And before Led Zeppelin I, II, III or IV were ever a glint in Jimmy Page’s eye, there was a band called The Yardbirds and they ruled.

The Yardbirds never came anywhere close to matching the mind-boggling chart dominance of The Beatles. They never were able to adopt the same effortless, sneering cool of Mick and Keith and the Rolling Stones. And they couldn’t physically dominate the stage with the same kind of explosive energy as The Who. They were simply the most talented, envelope-pushing band to emerge from the swinging London scene of the 1960s.

The Yardbirds were born in the smokey jazz clubs that dotted the London Metropolitan area in 1963. Their career was initially shepherded by a Swiss emigre, born in the Soviet Union named Giorgio Gomelsky. Gomelsky ran the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, where the Rolling Stones first cut their teeth. When Andrew Loog Oldham showed up one day and swiped the Stones from under his nose, Gomelsky vowed never to let that happen again.

Early on, The Yardbirds honed their blues chops while backing local heroes like Cyril Davies and American legends like Sonny Boy Williamson. Williamson swung through the scene in ‘63 looking to make a paycheck blowing his harp for hordes of young, English blues fans eager to hear the real thing for themselves. Eric Clapton entered the lineup around that time, then split just as soon as the band scored their first Top-5 hit, a bongo-fueled rave-up titled “For Your Love.”

No matter. Enter Jeff Beck, one of the most supremely talented musicians to ever pick up a Telecaster. That’s when things got really interesting.

With Beck on board, the Blues was sacrificed at the alter of psychedelia as the Yardbirds twisted their sound in new and unique ways on songs like, “Heart Full of Soul,” “Shapes of Things,” “Over Under Sideways Down,” and “Train Kept A Rollin’.” Fuzz pedals, sitar, and enough feedback to pin your eyes to the back of your brain. This became their hallmark.

The group’s bassist, Paul Samwell Smith quit sometime in 1966. Again, no matter. Jeff Beck simply phoned up his old mate, and one of the best session players in London, Jimmy Page, to fill in. It didn’t take long before Page swapped out four strings for six — Chris Dreja took over on bass — and for a supremely brief moment in time, the Yardbirds could rightly boast the greatest two-guitar lineup ever conceived.

This version of the band only recorded a few songs together before Beck himself departed. The best is called “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago.” The unrealized potential that lives in the grooves of that single, galloping 45 remains one of the greatest “What-if’s” of that entire era.

When Beck left in 1967, Page naturally took the reins. Or he tried to anyway. The band’s management called in a ringer, a renowned pop producer named Mickie Most, to help pilot The Yardbirds back to chart dominance. But when the time came to record, Most’s instincts ultimately failed him. Page could see the future and wanted to record heavier, twisted material; songs like “Dazed and Confused.” Most forced them to lay down treacly pop compositions like “Ha Ha! Said The Clown” instead. The results were obvious.

The final epitaph for the Yardbirds was best summarized in a 1970 essay written by one of their most ardent acolytes, rock critic Lester Bangs. “The Yardbirds for all their greatness would finally fizzle out in an eclectic morass of confused experiments and bad judgments,” he wrote. “Because the musicians in the Yardbirds were just too good, too accomplished and cocky to do anything but fuck up in the aftermath of an experiment that none of them seemed to understand anyway.”

Recently, I had the opportunity to talk to Jim McCarty, the Yardbirds drummer and one of the only living members of the band who was along for the entire ride. Together we dove into the entire, incredible story of the Yarbirds. We also talked about the tragic legacy of frontman Keith Relf, and the unique differences between the Yardbirds’ three, iconic guitarists.

Let's go back into the past a little bit and begin at the beginning. The Yardbirds started out in 1963. How did you initially come together as a group?

I was at school with Paul Samwell-Smith, who was the bass player for the band, and we were very close. We had a little group at school, and we used to play American Rock and roll. Early Elvis, Buddy Holly and all of that stuff, from when we were about 17. Then we both left school, and then I bumped into him somewhere locally, because he lived quite close to me. We lived in the South-West of London. I think I saw him at a pub or something. So, we had a beer together and, he said, "Well, you've got to come around and listen to this record called Jimmy Reed Live at Carnegie Hall."

It was like R&B, what we used to call R&B, but it was Jimmy Reed. I loved it, and then from there he said, "Oh, well you've got to come see this group called The Rolling Stones, they're on locally in Richmond." So, we went up and saw them, and it was before they even had Charlie [Watts].

Oh, wow!

It was ages ago! From there, we all used to hang out in a pub in Kingston upon Thames, which was there where we lived. Paul met Keith Relf, and they had a little Blues band together. It was called The Metropolis Blues Quartet. I went to see them. Keith was playing – he looked really good – and then I met up with Chris Dreja and Top Topham. We decided to start a similar band, playing all that sort of music like Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, and all that stuff. It all sort of hit London at the about the same time, but it was very underground. It wasn't on the radio or anything like that.

To make a long story short, we got together in the end with Keith and Paul, because they were playing the Country Blues type of thing, and they wanted to get heavier. From there we developed The Yardbirds. Our first gig we played Eel Pie Island with Cyril Davies. Cyril liked us and he invited us to do some shows that he couldn't do, in his own sort of club in South London too.

Right.

Then we heard about The Stones playing the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond. They played there for a long time. Keith and Paul -- they sort of managed the Yardbirds -- went to see Giorgio Gomelsky who was the promoter of the club, and said, "We've got a big band. Come and see us, we can take over." So, he came and saw us rehearsing. He told me later that he was walking up the stairs and he heard us rehearsing. He heard us doing one of those buildup things, which they called the Rave-Ups after a while and he thought, "Oh well, they're a good band and they're sufficiently different to The Stones. I'll sign them." That was before he even saw us. So, he signed us, and we went from there.

Giorgio Gomelsky is really a pivotal character to the music scene during that time. As you said he was with The Stones, until Andrew Loog Oldham came over and snatched them up. Then shepherded you guys for a while. Can you tell me a bit more about what he was like?

He was a bit of a crazy guy. He was very continental. By that I mean, very sort of European, very French-Bohemian sort of thing. He was a mixture of nationalities. I think he was a bit of Italian, and Russian, and Swiss. He'd smoke French cigarettes, and coffee, and all of that. So, we thought he was very exotic.

What were his grand designs for The Yardbirds. How did he promote you? And what kind of advice was he giving you at the time?

Well, he had a lot of ideas. He got us to write songs. He said, "You're going to be hanging around a lot. So, you guys will use the time to write songs.” You know, that's a good idea. He had lots of mad publicity ideas. Like, we went around to the house of this MP, who had said something in the papers about Rock music, and we went and set up on his lawn. You know, things like that. If he had an idea, he'd ring you up first thing in the morning and get you out of bed. You know, "Come on, you've got to get out of bed, we're doing [the television show] Ready, Steady, Go." Or, something has dropped out and it's all last minute and all the rush all the time. So, he was crazy, but they were good ideas.

How did you ultimately migrate over from The Crawdaddy Club in Richmond to the Marquee Club in London?

All these clubs were starting to go into that sort of [blues rock] music. But, The Marquee was a traditional Jazz club really. Same as the 100 Club and The Flamingo. They were all jazz clubs, and then bands like us were coming along and playing all the R&B stuff and drawing in the crowds. There was more interest, and they were getting packed houses. The Marquee actually moved. It sort of coincided with our first date there. It moved from Oxford Street to Wardour Street. We played on the opening night with Sonny Boy Williamson.

Right, yes! I was going to ask you about that. That must've been quite a thrill for you to go from playing Jimmy Reed records to actually playing with someone like Sonny Boy Williamson.

It was really good fun. He was great! What a fantastic performer. What a showman he was. We met him because Giorgio was involved in The National Jazz Federation, and they would bring groups of Black Blues singers over and do tours altogether. Sonny Boy was in one of them, and he decided he'd like to stay in London for a bit. I think he liked all the groupies, or whatever. He liked the London life. I think he thought it was exciting. So, Giorgio said “If you're going to stay around you may as well play some gigs and we'll get The Yardbirds to play with you.” I think The Animals did as well.

Was he an intimidating dude?

He could be. He used to get quite drunk. He'd drink Jack Daniels, and I remember rehearsing a set with him when we did a recording, and when we'd go to record it he was quite drunk, and he played different songs. He just started them up, we didn't know what they were.

I'm sure as the drummer it’s gotta be pretty hard to try and keep the backbeat and the tempo when you don't know what the hell is going on.

We were all waiting there; “What's he going to do? What's he going to play next? What key is it for the guitar players?”

Yeah, that's true I guess. You'll be playing C and he's over there in B Flat.

I don't whether he actually told them or whether he just started playing and they had to guess what it was [Laughs].

So, The Marquee Club is largely where you record the album Five Live Yardbirds. Would you mind describing what that experience was like?

The sessions? Yeah, they were great! It was like a steaming. It was all standing, and it was very hot and sweaty. I don't know how many it would hold, but probably about 400 or 500 or something I think. Everyone would squash in and there'd be a great vibe, and everyone would go mad. They'd queue up right down the street when they came in.

How did Eric Clapton come replace Top Topham on guitar?

Well, Top Topham had a problem with his parents. His father was an artist and Topham was studying to be an artist. He was studying Art at Art School. He was quite young; a little bit younger than the rest of us. His parents didn't really want him to get into a group, they wanted him to study. I suppose all our parents did really.

Job security. Sure.

My mum wanted me to be a Stock Broker [Laughs]. They forced him really to leave, but he had to leave, and then we were quite lucky because Chris Topham came from this Kingston art school, and Clapton was there too. So, I knew them, and he already had a bit of a reputation because he played for a couple of other bands already. So, they asked him because he was coming into a group that had something going for it.

Had some juice.

He pretty well jumped in and was just trying things out. He would learn the same as all of us.

You know, “For Your Love” is one of my favorite songs of all time, and I can't imagine that song causing anyone, much less Eric Clapton to say, "You know what, this musical direction is not for me. I’m gonna go ahead and leave."

We were pretty desperate, because a lot of, well…desperate is a funny word, but there were a lot of bands that were in the same era, and they were all having hits. The Animals, The Stones obviously, The Beatles, the Kinks, they were all having hits except for us.

Right.

We tried things like “Wish You Would” and “Good Morning Little School Girl, “and they weren't really commercial enough to get into the charts. And then we actually played with The Beatles. They used to have a Christmas show every year. In 1964, we played with them at Hammersmith in a Christmas Show, and we were one of the support groups. There was a publisher there, and he had a demo of “For Your Love,” a Graham Gouldman demo. He thought this group would be good on this song. So, he got in touch with Giorgio, and we all loved it. Of course, Clapton said “It’s not really Blues.”

I mean, who cares?

Exactly [Laughs]. Exactly! But he did have a few issues going on with a couple of the other guys who he didn't really see eye-to-eye with [in the band]. He was very dedicated to what he wanted to do. He had his own ideas and his own bands, with what he wanted to do, and he was very ambitious as well. He was always going to be his own guy in the end.

I’ve gotta tell you, it's mind blowing to me that the same night you play with The Beatles at the Hammersmith for Christmas, that’s the night that “For Your Love” wandered into your orbit. That's just amazing! It's kind of one of those weird coincidences.

Quite funny, isn't it?

I think that song really demonstrates how clearly The Yardbirds were at the cutting edge musically speaking during that time. “For Your Love” is a harbinger of some things to come, psychedelically speaking. How much of that change in direction was organic between the remaining members of the band, and how much of that was shift was impacted by the arrival of Jeff Beck enabling to explore some territory you didn't anticipate going?

It’s a good question, because Jeff was quite different, as you know. Jeff wasn't a dedicated Blues guys. He more or less played everything. He loved Les Paul and he loved Electronic music. He loved The Beach Boys for instance. “Good Vibrations,” he went mad when he heard it. So, he was very much into experimenting, and lots of pedals and making different sounds. We loved it because we already had the Rave-Up sorted out and didn't want to stick to just playing Blues. It was too predictable.

Exactly.

And, we couldn't play Blues as well as Blues guys. We couldn't play it like Sonny Boy. We wanted to our version. So, we used what we picked out and then went from there.

You obviously recorded many songs in the U.K., but eventually made your way to America and visited places like Sun Studios in Memphis, and Chess Studios in Chicago. As a person who admired Elvis and Muddy Waters as much as you did, what was the experience like?

They were both Giorgio's idea. That was another thing. He came with us to The States. He had those ideas to go in those studios. It was a great idea. It was very funny because I think we just turned up at the studio, like it was one of those crazy things. We were in Memphis and we turned up there and he called up Sam Phillips. I don't know he got his phone number. Sam was out fishing, and Sam said, “Oh yeah, I'll come down and we'll start the session at 11 o'clock at night or something crazy.”

You recorded “Train Kept a Rollin’” at Sun Studios, correct?

Yes.

How many takes did it take to cut that one?

Well, Sam was doing the engineering, and he knew what he was doing. We cut it in a couple takes.

That's incredible.

“Mister, You’re A Better Man Than I,” we cut there. I don't know what else we did, but we did “Shapes of Things” in Chess.

A lot of people focus on the guitarists in the Yardbirds for good reason, but I want to talk about Keith Relf for a minute. I know you wrote a lot of songs with him, and he was obviously the lead singer of the band. I’m curious, what was he like as a person, and how did he handle or feel about being in a band where maybe the guitarist was more of the focus than the singer?

Yeah, that was very odd because he was a very obvious front man. When I first saw him playing with Paul I thought, this guy is a real front man. You know, when one looks at him, he's got the long blonde hair, he's got this sort of way with him. Everyone wants to mother him. Then, when Clapton was in the band, I noticed that he got a lot of interest, a lot of people looking at him or standing on his side of the stage when he was playing, which was unusual because the front man normally got all the attention.

Sure.

He got a lot of attention, more than Keith in the end. I don't know what Keith thought about it. I don't know whether he was jealous. He may have been, but it was never obvious that he was jealous. He had some good ideas, Keith, he was a creative guy.

Great harmonica player.

Yeah, he was very good. He loved Jazz, and he loved a lot of different music, and he had his own view on things, and he was a very spiritual guy. I really got on well with him. He was probably my best friend for a long time.

So, eventually Paul Samwell-Smith decided to leave the Yardbirds in 1966. Now you need a new bass player. You choose to go with Jimmy Page, one of the greatest session guitar players in London. How did that change the character of the band, when Jimmy Page came in?

Well, it was very odd actually, first of all, because originally, we tried Jimmy when Clapton left. He wasn't interested in those days, but Giorgio knew him quite well. I mean, it was a bit silly in a way, but they did well. Eventually [guitarist Chris Dreja] swapped over [to play bass], and actually did a pretty good job. He worked on it, and he did very well I thought, on bass. Then the two of them [Beck and Page] that was quite a harrowing experience with the both of them. They were trying to outdo each other. Such a massive amount of energy going on, on stage.

Did you ever have those moments when you’d be behind the kit and just like sit back like, “Wow, I don't even know what happening right now?”

Yeah, of course. They were few and far between because most of the time. They were really trying to outdo each other. So, it was a real mess. But, when it worked. They all played in the right places, and they were all firing on all cylinders. It was fantastic.

Did they ever have any disagreements between them?

No, they were great friends since, I think, they were about 16. I didn't realize that. I didn't know that they knew each other so long, but actually Jimmy told me fairly recently. There was definitely aggravation. I don't know where it came from.

A little bit of "hotshottedness?"

It's aggravation when they were playing, but not with Jimmy so much as Jeff. Jeff was a lot more nervous. A lot more strung out, and a lot more insecure I guess. Jimmy knew what he was doing. He was used to playing sessions and things.

The song “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” is one of the only recorded instances of the two of them playing together on a song. How did that one come about?

Well, Keith and I used to get together and write little songs. As I said, he was quite spiritual, Keith. We got talking, and we said let's do a song about being born again; about being reborn like the Buddhas talk about. Karma, and all this. You know, recognizing faces that I've seen before?

Sure.

So, we got the tune together, and the words, and then we went into the studio and Jeff and Jimmy got into it. Jimmy put that sort of riff down, “dun-dun-dun-da-da-dun-dun-dun.” Then Jeff did that solo, and everyone did really well. John Paul Jones played bass.

Wow! Was that done in a single day?

Yeah, we took a day. That was no problem. A pretty long day, I think. Maybe we mixed on another day. I think maybe some of the solos were done on another day, I can't remember, but the track was together that day.

I was reading about some of the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars tours you guys did in the mid ‘60s, and that sounds like quite a brutal operation. Shuttling around the U.S. in a bus full of people, playing every single night. That had to be tough.

Yeah, it wasn't quite as bad as you've made it. We did have hotels. But, it wasn't a tour bus. It was just a regular bus.

Like a Greyhound?

Yeah. It wasn't a tour bus with beds and all that. I don't think they had tour buses. So, we had hotels. Occasionally, we went to two gigs in one night, and it was all down South. Most of it was in very weird territory. People that walked on quite behind everyone else. People would be shouting out "Oh no, turn that guitar down." Or, "That guitar is too loud!"

Go to a Rock and Roll show and tell them to turn the volume down. That makes no sense whatsoever.

I know, but we were playing with these other bands. You know, Sam the Sham and Gary Lewis. Yeah, they were very down island. They weren't really heavy rock, were they?

I’ve said this before, but if I could go back in time just for the concerts, those gigs you did with Tina Turner and The Stones in England at the Royal Albert Hall are pretty high up on my list.

Oh, that was great. What an incredible lineup, Tina Turner, and Ike Turner as well. I like Tina. She was really good, too, and The Rolling Stones, and us with Jimmy and Jeff. It was a good show.

Who were your favorite bands to play with during that era?

I loved playing with all of them, really. The Stones were great. The Kinks were brilliant in those times, and they got a lot better with all the songs when “Sunny afternoon,” and all that stuff came out. But the early days, I don't know if they were quite as good. The Stones, I think, were really good. When they started, they were great. The Animals were good, because Eric [Burdon] was very good. And I think that The Who were really good.

The Who were explosive. I mean, literally sometimes.

They were very, very powerful. It's very difficult to play with such a good band. It's hard.

I was listening to The Yardbirds '68 live album the other day. It struck me how obvious the direction Jimmy wanted to go to with the band’s music. Heavy, psychedelic songs, like “Dazed and Confused,” “White Summer,” and that lengthy jam on “I’m a Man.” But, then you also had Mickie Most, your producer at the time over here, saying “Let’s cut ‘Ha Ha! Said the Clown,’ for the next single” What was that tension like for you?

Oh, that was horrible. It really was horrible. We sort of lost it somewhere along the line, and to give up our road to Mickie, just for the sake of it, it was a big mistake. We did so many crap songs. I mean “Ha Ha! Said the Clown” had already been found by the Manfred's. That was crazy. That was a big mistake.

The Little Games album has its moments for sure. There was certainly the potential there to do something great. How did you balance Jimmy’s heavier, psychedelic inclinations against Mickie Most’s desire to score a chart hit?

It was very, very difficult I think, because we were very, very highly pushed for playing live. There was no big money in record sales compared to later on, Led Zeppelin time. Everything was about singles, and when are you going to get your next single out. What's your single going to be? And, we weren't going down that road, we were doing album stuff. We were desperate for a song. When Paul and Jeff left, we didn't quite have that chemistry

Who was it in the group that came across the Velvet Underground. I noticed that “I’m Waiting For the Man” got thrown into the setlist quite a bit during the later years.

Well, they were a band that was around, and we played with them a few times. They were a bit odd, they were strange, you know?

I'd say so.

We played with them in some sort of hippie wedding in Detroit. It was very odd. The Yardbirds and The Velvet Underground playing together at a wedding. How weird is that?

That sounds like one of the most insane things I’ve ever heard.

Yeah!

So, around the middle of 1968, you and Keith Relf decide to go off and do something different. Jimmy Page meanwhile wants to stick around and thus, the New Yardbirds; aka Led Zeppelin. How did you feel about leaving the band, and what caused you to make that decision ultimately?

Well, it was a relief for a start, because it was just going on and on. It was just unstoppable sort of thing. It was very, very tiring. We needed time to sort ourselves out, and we didn't get that. There was no opportunity. It was like, oh, if you disappeared for six months, everyone would forget you in those days [Laughs]. Looking back, we could've done [more], but that's very easy to say, isn't it?

True, but to your point, you had been going since '63 by then. Five years of recording sessions, and tour dates…

Yeah, photo sessions and interviews, and everything else.

You had a seat that not many people in history have ever occupied. You got to play with three of the greatest guitarists of all time both together and separately. I’m just wondering from your position, what was the difference between playing with all three of those guys? Beck, Page, and Clapton? What did they bring to the table, and what makes them so unique?

In terms of the musicianship?

Sure, musicianship.

Jeff was the best because every time we played, it was different. It was completely spontaneous, and it was fun because sometimes things would happen. Like Jazz. It was like Jazz. Playing off each other and all that stuff.

Jimmy had it all worked out. He had been used to the studio, playing in the studio, and he wanted to work the song out. So, he had everything worked out. He didn't improvise so much as Jeff. Jeff would totally improvise.

And, Eric was sort of in a narrow Blues-y thing. It's a bit unfair, because we were just really starting.

He was very young. 18 or 19 then.

And, he was just trying to get his technique together, really.

How about in terms of temperament? How were they different at people?

Well, their temperaments, yeah. The easiest would've been Jimmy, because he was cool and very businesslike about it. He didn't lose his rag, like Jeff. Jeff would lose his rag a lot. He'd go mad and lose his temper, and it was too much for him. He'd kick an amp off the stage or something, or smash his guitar, sort of mad things.

You saw that in Blow Up.

Eric would be very sulky. He'd be in a mood, all sulky and not want to talk to anybody.

Through the years, and after the breakup, did an opportunity ever arise where you might've gotten together with all three of them to play again?

Yeah, I think it sort of came close. Jeff was very odd because he doesn't tell you straight, you know? I thought it might be a good idea that we all got together, and he said, “Oh, yeah, I'll sort of think about it.” He wouldn't say, “No, I wouldn't do that, because Keith's not there.” I think that sealed it. They wouldn't want to do it with what's his name, from Aerosmith.

Steven Tyler.

I mean that was a possibility, but…

As you kind of alluded to, Keith Relf died in 1976 after getting electrocuted while playing guitar in his basement. If he had stuck around longer, what do you think he would've done with his career, and do you think you guys might’ve played together more?

Yeah, I think so. Yeah, I think he would've come back into things. He wasn't very healthy. He wasn't a healthy guy. He needed to be stronger health wise. I think he probably would of come in. He would come back.

A lot of people speak about The Yardbirds as a sort of prelude. A prelude to Eric Clapton and Cream. A prelude to Led Zeppelin. A prelude to Jeff Beck’s career. As you know better than most however, the Yardbirds were a great group on their own right. To your mind, what was it that made The Yardbirds so unique in British blues scene in the '60s? And what sets them apart from all those other bands now?

I think we were in it for the music. We weren't in it for the show, or the money, we never really made huge amounts of money from that. We split up too soon, and we weren't in it for the showbiz. We just loved the music, and that was it. We wanted to make the music different. We wanted to make it sort of futuristic. I guess that's why it still sounds good.