30 Years of Temple of the Dog: The Mournful Tribute Album That Defined an Era

With an exclusive look into London Bridge Studio in Seattle where it was recorded

The compact control room is dark and loaded with heavy silence. With no client to host this morning, the typically warm, wood covered walls are shrouded in black. The most powerful sources of illumination come from the various computer screens flanking the enormous, 30-track Neve mixing console splayed out in front of me. Just beyond, the soft yellow glow emanating from the live room provides enough light to make out the label stamped into the board’s heavy wooden frame. It reads in all-caps: LONDON BRIDGE.

“Want me to play something?” the studio owner Eric Lilavois asks. “Yeah, that’d be great!” I reply.

Eric fiddles around with his phone and some of the equipment for a few moments. Suddenly the sound of a solitary electric guitar twinkles out of the massive pair of monitors hanging from the ceiling. Then a voice; one of the most iconic voices to ever emerge from the gloomy confines of the Pacific Northwest bursts into the room.

“I don’t mind stealing bread from the mouths of decadeeeeeents.”

Almost instantly, the hairs on my forearms stand up straight as a field of wheat. A chill goes down my back, and my skin turns into a patchwork of garbled braille. The enormity of the situation hits me like a tidal wave. Chris Cornell stood in this exact same spot 30 years ago. He was here, in this room, listening to this same exact song that he had just recorded in the booth just next door. He heard it through this same exact board and through these same exact speakers. Until they invent time travel, this is about as close as it gets to revisiting the heady, inspired gloom of 1990.

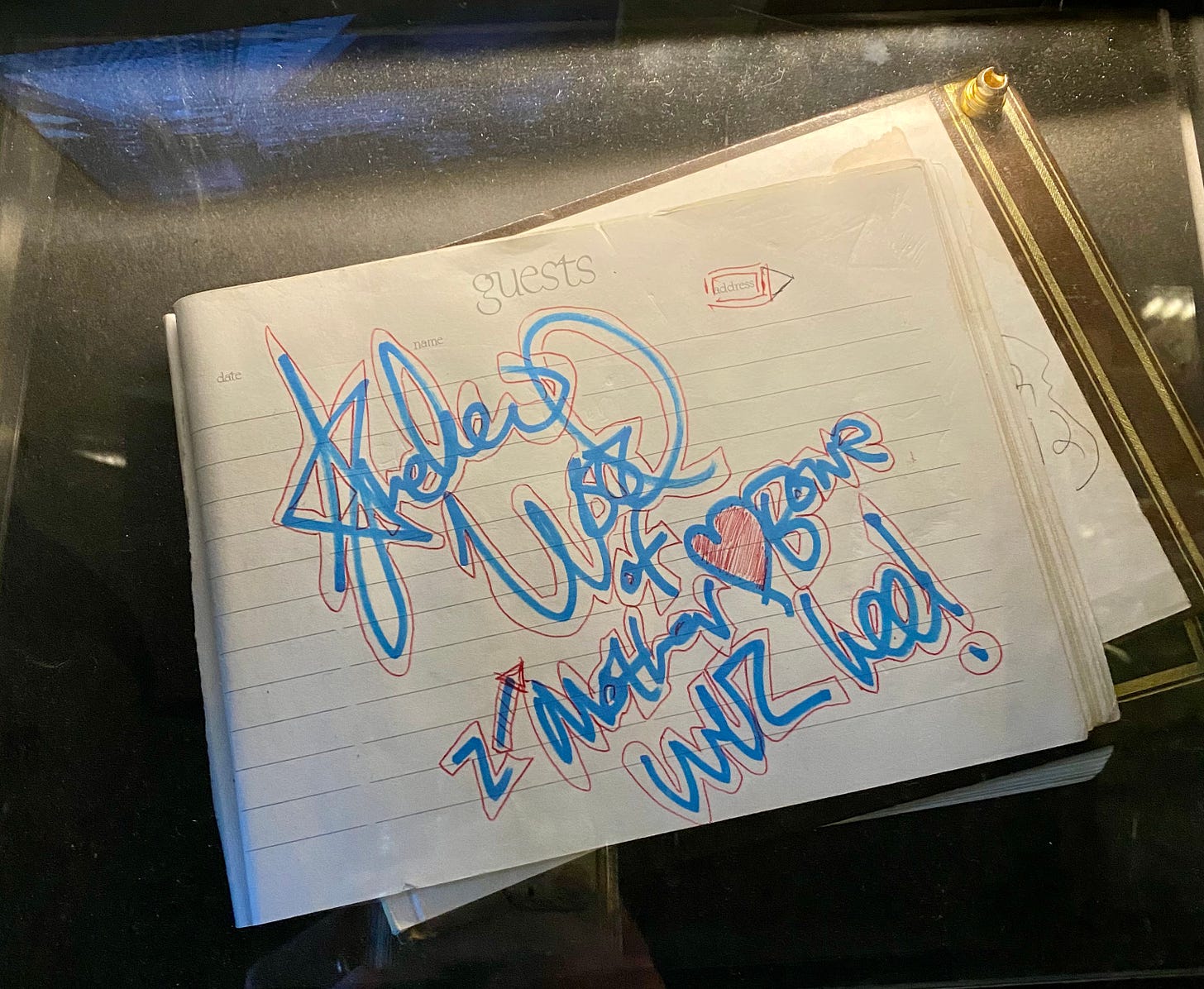

The tragic spark that inspired the creation of Temple of the Dog greets your eyes nearly the minute you walk into London Bridge Studio in Shoreline, WA. After passing through the front hallway, you arrive at a glass case filled with a variety of musical ephemera. T-shirts, tapes, etc. It’s the item on the top left that really draws your eye, however; a single page of a flipped over guest book.

The words are scrawled across the blank sheet in blue marker and outlined by red pen. The scattered signature of Mother Love Bone frontman Andrew Wood. Instead of an “A,” however he used a five-pointed star to mark the first letter of his name. Clearly, this was someone with big dreams, and a supreme confidence in his ability to see them through.

Mother Love Bone occupied London Bridge for the first time in November 1988 to record their debut EP Shine. It dropped in the spring of the following year. Head just around the corner and into the studio’s live room and you can play the same exact Yamaha grand piano Wood used to play and record the song “Chloe Dancer/Crown of Thorns.”

Wood, along with Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament, Bruce Fairweather and drummer Greg Gilmore returned the following Winter to put the finishing touches on their full-length debut, a record ultimately titled Apple that many projected would help catapult Mother Love Bone to the very top of the rock and roll hierarchy. Sadly, it wasn’t meant to be. Wood died on March 19, 1990 shortly after his girlfriend Xana La Fuente discovered him in a comatose state after overdosing on heroin.

While Wood’s death hit many in the Seattle music scene like a sledgehammer, few were left more stunned and hurt than Chris Cornell. “It was heavy,” Soundgarden’s roadie Eric Johnson told me. “It was not a fucking great moment. Chris was crushed, obviously. He was the closest of all of us to Andy.”

Wood and Cornell had lived together for a time in the late ‘80s, sharing a house at 426 Melrose Avenue East on Capitol Hill in Seattle. During that period, they had become extremely close. This was in spite of the fact that in almost every conceivable way outside of their love of music, Chris Cornell and Andrew Wood were near-diametric opposites of one another. The former was quiet, with dark curly hair and sharp features; intense and magnetizing, but with a goofy personality that undercut his more stoic tendencies. The latter was almost cherubic in appearance, gregarious, outgoing: the life of every party.

“I didn’t deal well with Andy’s death,” Chris admitted. “After he died, numerous times I’d be driving and I would look out the window and I thought I saw him. It would take me five minutes to update to the moment and realize, ‘No, he’s actually dead.’”

Wood looked up to Chris in many ways, and Chris always admired elements in Andy that he wished he could embody in himself. “Andrew was in awe of Chris,” Kevin Wood told me while I was researching my book Total F*cking Godhead. “I remember him playing demos Chris was making and just really being in awe of his ability to write.” Though Wood was slightly more prolific, Chris had a more sophisticated sense of music. “He knew a lot more chords than Andy, I guess. [Andy] did feel like he was jealous in a way.”

For his part, Chris admired Wood’s carefree spirit. “He seemed to really have no editing voice in his head at all,” Chris told “Pierre Robert of 93.3 WMMR. “I had an editorial staff in my head arguing about what I’m doing. I took that definitely from him as a lesson to just chill out and be creative.”

Chris first learned about Wood’s death while on the other side of the country, performing in Brooklyn with Soundgarden. As quick as he could, he hopped a flight back west and made it to Harborview Hospital where Andy and his family had all gathered. Collectively, they decided to wait until Chris showed up to pay his final respects before pulling the plug. It’s what, they assumed, Wood would have wanted.

“On the one hand it’s like ‘That’s really cool,’” Chris told the filmmakers behind the Andy Wood documentary Malfunkshun. “On the other hand [it] was like, ‘Well, that’s really creepy. That’s really awful.’ His family is all sitting there waiting to get this over with. So that made it especially weird. I didn’t wanna feel like the guy that was holding up this inevitability.”

Not long after Wood died, Chris once again hit the road with Soundgarden. While on tour, he composed a pair of songs in tribute to his departed friend. The first was a slow-simmering ballad titled “Say Hello 2 Heaven.” The second, an exuberant rocker called “Reach Down.” They weren’t Soundgarden songs, that much he knew, but he wanted to do something with them regardless.

After returning home to Seattle, Chris’s demos worked their way into the hands of Wood’s bandmates Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament. They liked them enough that they decided to work with Chris to record them as a tribute to their departed friend. They also roped their buddy Mike McCready into the project to play lead guitar.

Originally, the group thought about re-recording several of Andy’s own songs to go with the one’s Chris already had in hand. But when they got a bit of pushback on that idea, they decided instead to write and record a whole bevy of entirely new material instead. With that decision made, Chris brought his Soundgarden bandmate Matt Cameron along to play drums and thus, Temple of the Dog was born.

The name of their band was taken from a line in “Man Of Golden Words,” a song Wood had written for Apple. It’s a heartbreaking stanza in which he reveals both his truest desire along with a stunning self-appraisal.

“I want to show you something, like joy inside my heart / Seems I been living in the temple of the dog.”

Chris and the band started rehearsing and workshopping the material for Temple of The Dog in an eight-hundred-square-foot cottage built on Chris’s grandparents’ property near the Seatac Airport. In addition to “Say Hello 2 Heaven” and “Reach Down,” Chris also wrote the music for “Your Savior,” “All Night Thing,” “Call Me A Dog,” and “Hunger Strike.” He also whipped together lyrics based on music Gossard and Ament gave him that ultimately became the songs “Pushin Forward Back,” “Four Walled World” and “Times of Trouble.”

Incidentally, Gossard and Ament had also recently passed along a tape of music to an unknown singer-songwriter down in San Diego named Eddie Vedder. Vedder set his own words to the pair’s music, recorded them to a tape of his own, the infamous “Momma-Son” demo and mailed it North. The duo was impressed enough by his creations — “Alive” “Once” and “Footsteps” — to invite him up and see if he might front their next band.

Vedder flew into Seattle for the first time on October 8, 1990. In a strange twist of fate, just a few days earlier, he had been down in Irvine, California watching Soundgarden perform at an outdoor amphitheater. Just another fan among the crowd. Now his new, potential bandmates decided to bring him along to their sessions with Chris.

At the time, the band was working on “Hunger Strike,” but it was frustrating. Chris always envisioned singing “Hunger Strike” with a high, soaring register accompanied by a lower harmony to round it out. He figured he’d be able to handle both parts himself. As he was working through the arrangement with the rest of the band though, singing at the highest reaches of his voice, he felt a presence move in behind him. Vedder had been sitting in a corner, affixing strips of duct tape to a drum. He couldn’t help noticing that Chris kept having to cut off one part of the vocal to start the other.

There was only one microphone set up in the room, but Eddie signaled to Chris that he had an idea. It was a bold move from the out-of-towner, but Chris made space for him in front of the mic. Suddenly, the two men were singing the chorus together, wrapping their voices around one another. Chris was free to blast off into the stratosphere while Vedder was right there next to him, keeping his feet on the ground.

From that rehearsal, Chris realized that including two singers could only work to enhance the overall composition. He also only had one verse written, and knew that if it was sung by two different voices, he wouldn’t need to write a second. Originally Eddie Vedder walked into those sessions as a fan. By the end of the night, he walked out a peer. More than that, he’d become a friend.

“I’m gonna close the doors,” Eric told me as we enter the tight, closet-sized vestibule. Immediately all sound in the room drops out completely. Any trace of reverb is gone. The air itself feels heavy, and in a moment it dawns on me. This is the room where Chris Cornell recorded his vocals for “Call Me A Dog.”

I don’t have to make the case here for his place among the pantheon of the greatest singers of the last 50 years. You can find all the evidence you in songs like “Cochise,” “Fell on Black Days,” “4th of July” and “Seasons.” But if you’re looking for exhibit A; the greatest vocal performance that Chris ever recorded, “Call Me a Dog” is the one.

Incredibly, Temple of the Dog was recorded in just 14 days spread over a couple months. Most of the work was done on weekends to save money. “There wasn’t a budget for it really,” engineer Dave Hillis told me. The band had to get creative and cut costs wherever they could. “It was used tape, so there were old tracks from whoever recorded on it before,” Hillis added.

The stakes were emotionally high, and commercially low. “They seemed to treat it as though it was a vanity project for me,” Chris remembered of his attempt to describe Temple of the Dog to his label, A&M Records. He and the rest of the band weren’t out to make a platinum record. They were merely trying to honor their friend in the only way they knew how. “The whole situation was just so non-pressure-filled,” Gossard said. “Nobody expected this to be anything, so when we just went in and [recorded] it the record company wasn’t around. We basically paid for it ourselves.”

Temple of the Dog hit the shelves initially on April 16, 1991. It didn’t sell very well. 70,000 copies at best. Not even enough to crack the Billboard Top-200. Eventually, millions would discover this essential suite of 10 songs after Eddie Vedder and Pearl Jam hit it big with their debut Ten — which was also recorded at London Bridge — and Soundgarden finally broke through with Badmotorfinger. They would soundtrack weddings, picnics, parties and yes, funerals for decades to come while also becoming defining sonic touchstones of the era itself.

Ultimately Temple of the Dog’s truest legacy isn’t the platinum plaque hanging on the wall of London Bridge. It’s in the emotion-racked goodbye to a friend who meant so much to so many. It’s in the way Chris’s voice soars atmospheric heights in tribute to Andy and drops to Grand Canyon-level lows to express his grief that he’s no longer around. It’s in the way it kept his memory alive, even after his spirit moved on.

Its legacy is also the hearty welcome to a talented newcomer to the scene, Eddie Vedder; the one who would pick up the mantle where Andy left off. It’s in the way the band cajoled Mike McCready to erupt with volcanic fury during his first recording sessions ever while laying down the solo on “Reach Down.” It’s also in the way it gave Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament hope that there was a future for them after all.

Unfortunately, Temple of the Dog has a new legacy. For so many years, and on so many stages around the world, Chris would sing “Say Hello 2 Heaven” and dedicate it to Andy. Many times people approached him to use the song for different purposes to tributize different people, but he always refused. “Say Hello 2 Heaven” was a specific expression of grief for a specific person.

It’s evolved beyond that now. Its legacy is now also a tribute to the man who was there for Andy in all those times of trouble. It’s for the man who wrote it.

One of the top three albums of all time !